Just as the mobilisation was an active period in April, the end of June is the season “FINALE” ! At this point, there are no more arrivals, only departures of scientists. This also means a final series of instrument deployment operations!

As expected, the ice progressively melts around the community. It forces the team to find other, safer, skidoo parking lots. The team migrates three times to other bays, on June 20th, July 2nd and again on July 8th. The ice close to the community is melting fast !

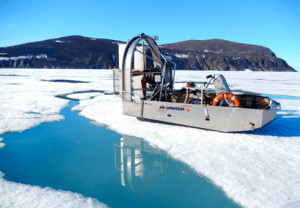

Unfortunately, the airboat could not be delivered to the ice camp on June 23rd, due to persistent low ceiling. We did not have many options left to safely transport researchers and equipment to the ice camp location. We began to look at the weather forecast and ice conditions more than once a day anticipate when the ice would no longer support the weight of the skidoos … or just break up and drift away.

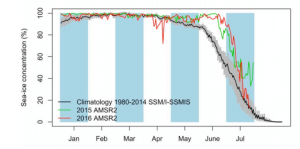

Figure produced by Emmanuel Devred and Maxime Benoît-Gagné

Figure produced by Emmanuel Devred and Maxime Benoît-Gagné

Will Green Edge succeed in extending the sampling season through the melt season and capture the phytoplankton spring bloom?

Not only are visits to the ice camp compromised without the airboat, but Eric Brossier’s travel from his sailing ship, Vagabond, to the community has also become perilous. It takes much more time and risk to use a series of motorised vehicles than just an airboat. At one point, Eric walked across the ice from the Vagabond to the Hamlet (1hour). The next week, he had to walk to the edge of the ice surrounding Vagabond, then take his small boat across the open water to the community (1 hour), hop in a truck from the basecamp to the skidoo departure point (15 min) and then lead the convey of skidoos to the ice camp (45 minutes). He repeated this scenario every 2 days (see Vagabond post) !

On July 10th, there was a last chance for the CCGS Amundsen to deliver the airboat. Communication is difficult in the Arctic, especially between a moving ice-breaker and research operations at an ice camp. Nevertheless, early morning discussion with the Amundsen’s chief scientist , Jean-Eric Tremblay, allowed us to shift our day station to a night station. For those familiar with northern research, the operation schedule is always changing. We can not escape this fact! The ship was sailing faster than expected; it was finally decided that the ice camp researchers would leave town 15h to be there in advance of the new ETA of 19h. Once the team leaves the community there is no way of easy means of communication between the ship and the scientists on ice. At 16h, I got a VHF call from Debbie, our land base logistics coordinator, asking me to contact the Amundsen. The ship was moving quickly and now expected to meet us at 17h. As luck would have it, we departed early and could make the rendez-vous as we were already on site! After verifying a meteorological point about the surrounding ceiling/cloud level, the helicopter pilot, Guillaume Carpentier, along with the captain of the Amundsen, Alain Lacerte, give it the go-ahead and launch the helicopter departure. All eyes and ears are on alert; Jade, Jaypootie, Eric, Makoto and I are screening the sky to see the helicopter flying towards us with the airboat at the end of a sling rope. There it is FINNALLY! As all of our light sampling gear is flying around in the helicopter-created local windstorm, we can only focus on the landing of the airboat. The pilot did not even land the helicopter itself, as the airboat touches down, he let down the sling with it and goes back to the ship.

On July 10th, there was a last chance for the CCGS Amundsen to deliver the airboat. Communication is difficult in the Arctic, especially between a moving ice-breaker and research operations at an ice camp. Nevertheless, early morning discussion with the Amundsen’s chief scientist , Jean-Eric Tremblay, allowed us to shift our day station to a night station. For those familiar with northern research, the operation schedule is always changing. We can not escape this fact! The ship was sailing faster than expected; it was finally decided that the ice camp researchers would leave town 15h to be there in advance of the new ETA of 19h. Once the team leaves the community there is no way of easy means of communication between the ship and the scientists on ice. At 16h, I got a VHF call from Debbie, our land base logistics coordinator, asking me to contact the Amundsen. The ship was moving quickly and now expected to meet us at 17h. As luck would have it, we departed early and could make the rendez-vous as we were already on site! After verifying a meteorological point about the surrounding ceiling/cloud level, the helicopter pilot, Guillaume Carpentier, along with the captain of the Amundsen, Alain Lacerte, give it the go-ahead and launch the helicopter departure. All eyes and ears are on alert; Jade, Jaypootie, Eric, Makoto and I are screening the sky to see the helicopter flying towards us with the airboat at the end of a sling rope. There it is FINNALLY! As all of our light sampling gear is flying around in the helicopter-created local windstorm, we can only focus on the landing of the airboat. The pilot did not even land the helicopter itself, as the airboat touches down, he let down the sling with it and goes back to the ship.

The airboat is down! Jaypootie is impressed by its dimensions (1,8 x 4,3m); he expected a smaller boat. As time is quickly flying by, we have to divide up the tasks. There is still a sampling station (3 hours) to carry out before making our way back to town. Jay and Eric are filling up the airboat with oil and gas and when the critical moment arrives, will it start properly? Jade and Joannie are happy to hear the airboat break through the magical silence of ice operations while they are deploying the C-OPS, it is working! We all get a turn piloting the airboat and feel its ability to transit over the rough ice surface, melt ponds and open water.

The airboat is down! Jaypootie is impressed by its dimensions (1,8 x 4,3m); he expected a smaller boat. As time is quickly flying by, we have to divide up the tasks. There is still a sampling station (3 hours) to carry out before making our way back to town. Jay and Eric are filling up the airboat with oil and gas and when the critical moment arrives, will it start properly? Jade and Joannie are happy to hear the airboat break through the magical silence of ice operations while they are deploying the C-OPS, it is working! We all get a turn piloting the airboat and feel its ability to transit over the rough ice surface, melt ponds and open water.

Eric Brossier is the designated airboat pilot. The boat takes a little more time than the skidoo convey to reach the community. Once there, what a surprise: with high tide (Ulit) there was no longer ice access to the beach! What a perfect timing to have the airboat that night to make the return smooth, dry and safe.

Contributions of the airboat

- The airboat allowed a two week extension (11-22 July) of full profile stations in heterogeneous conditions of broken and drifting ice and open water, until the Amundsen completed the melt season with a last station on July 28th.

- This extension allowed us to capture the sinking, sustained and changing composition of the PSB

- The experienced eyes of sailor Eric noticed a drifting red buoy on July 13th, which happen to be an expensive instrument that was suppose to be still recording data from the seabed for a year time series: a lander. Just before the lander drifted out of the fjord into the open region of Baffin Bay, we were able to install a SPOT, enabling the CCGS Amundsen to locate and recover it 2 weeks later.

- Like every spring season, a lot of Inuit leave the community on their skidoos for two to three weeks and go to their cabins ‘on the land’ waiting for open water to bring their boats back to the community. This year, a family spent more time than expected waiting for the water to open and did not have enough milk for their young daughter. As the airboat was the only vehicle going back and forth between the community and the ice camp location, we helped by delivering milk to the family. They were able to access the community a couple of days later by boat.

Photo credits: Eric Brossier and Joannie Ferland